The True History of the AKC and James Watson

August 24, 2010

Once again I find myself in the position of apologizing for the lateness of an issue of the Dogcrazy Newsletter. This wasn't supposed to happen. Months ago, I penned a short piece on James Watson, best known as the author of

The Dog Book, figuring that it would give me the option, if I was ever short of time, to plug it into one of the newsletters. That was what I intended to do for this August issue. Before sending it out, for some reason, I decided to google Watson and I became furious at what I found. Or, rather, furious at what I failed to find. After that things just got out of hand, swelling like a mushroom cloud.Let me make what may seem like a bold statement:

I consider James Watson to have been the most influential man in all of American dog history. Others may challenge this and they could well be correct. But, with the exception of one series of articles (see the P.S.), his name barely appears, except in reference to The Dog Book. I'm amazed that he has gotten such short shrift in the history books and, in this newsletter, I'd like to try to set the record straight. (The photo that heads this newsletter is taken from the Philadelphia paper which printed Watson's obituary in 1915.)I thought I would tie together that goal with what I'm doing in the ebay store. I had finished listing almost all of the breed books in my collection and was already moving on to the other volumes on the shelves. What better way, I decided, than to kill two birds with one stone. So, I thought I'd really kick things off by listing some of the rarest books in my collection. As you will see, these involve James Watson. I apologize, in advance, for the length of this newsletter, but because of the dearth of information on Watson's role in history, I felt duty bound to be as complete as possible.

Let me take you back to the days before there was an American Kennel Club and the birth of that organization. If you've read anything about the history of the AKC, it probably goes something like this: On September 17, 1884, a group of 12 gentlemen met in one of the rooms of the Philadelphia Kennel Club and agreed to start a national kennel club. And, voil

á, the AKC was born.Now I want to ask any of you who have been involved with dog clubs to answer a simple question: how likely is it that the American Kennel Club was founded in such a courteous and congenial manner? Serious dog folks are dedicated, passionate and opinionated. They can also be jealous, petty and self-absorbed. Factions rise and fall among dog fanciers, sometimes based on the breed raised, the line chosen or the type preferred. There are frequent personality clashes and ambition often gets in the way. Most serious fanciers are absolutely convinced that their opinions are the only ones that are correct. Why, pray tell, should we think that dog fanciers in the 1800s were any different? The truth is that the American Kennel Club was born from a simmering cauldron of divergent opinions, interests and personalities. The politics and turf battles that took place molded the AKC into the highly efficient organization that it is today.

England's Kennel Club was founded in 1873. Dog shows began in this country in 1874. No awards were given at the first three shows, but on October 7, 1874 a show was held in Mineola, New York, which operated under the English Kennel Club rules. This is considered the first American dog show. A day later, the Tennessee Sportsman's Association, headquartered in Memphis, held both a bench show and field trial. Again, they used the English Kennel Club rules for their bench show. Other shows in Michigan, Massachusetts, Kentucky, New York, Tennessee and Vermont followed.

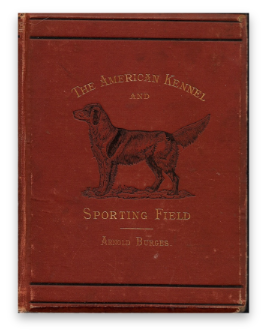

In 1876, Arnold Burges published the landmark work,

The American Kennel and Sporting Field. (See our ebay store for this rare volume). It included the first stud book published in America and the first record of field and bench shows. It was, however, limited to mainly Pointers and the Setter breeds, with nine entries for spaniels thrown in.Burges was from a very wealthy and prominent family that included congressmen and judges. He graduated from Union College in 1860 and began his career as a attorney, but his passion for gundogs soon led him in another direction. He began writing about dogs and hunting and, in 1872, joined the staff of the Pennsylvania paper, The Herald, later moving to The Evening News. In 1873, he was named as editor of The American Sportsman. (Later expanded, the paper's name was changed to Rod and Gun. Still later it would be merged with

Later, in 1876, the National American Kennel Club was founded, in Chicago, though its permanent headquarters was in St. Louis. Composed of field trial advocates, its President was Dr. Nicholas Rowe and Arnold Burges served on the board. Rowe was a physician but, like Burges, he had become obsessed with gundogs and he began to write about them. (His early writings, in publications like

Rod and Gun, were penned under the pseudonym "Mohawk.") And, like Burges, he imported Llewellyn Setters and was one of their prime advocates. Dr. Rowe had helped organize that first bench show in Mineola, New York and, along with his friend, Major J.M. Taylor, had helped organize the Tennessee group's first field trial. On that basis alone, Dr. Rowe was a big name in the fledgling world of American dogdom. There was something else, though, that gave Dr. Rowe additional clout.In 1876, Dr. Rowe had moved to Chicago to take over the struggling paper, the Chicago Field. He completely revamped the paper, penning strong editorials and attracting the best writers. Information about gundogs was featured prominently in the paper. Dr. Rowe had owned Irish Setters, but from 1872-1874, he had imported a number of English Setters directly from Richard Purcell Llewellyn. Under his leadership, the Chicago Field became the leading sporting paper of the day and a prime promoter of the Llewellyn (Llewellin) Setters. By 1881, the paper had become so popular all across the country, that the name was changed to The American Field. It remains the oldest continuously published sporting journal in this country.

The National American Kennel Club promptly announced that it would publish a stud book and Rowe was appointed editor. Work on the project was slow, however, and the

first volume of the National American Kennel Club Stud Book was not published until 1879. Also included in the book were the constitution and by-laws for the club and its rules for both bench shows and field trials. There were the results of the eight bench shows that had taken place in 1876-1878, including the first Westminster, as well as the awards given at the five field trials.It's interesting to note that, by the time that first NAKC stud book was published, Arnold Burges was no longer on the group's board. One wonders if he and Rowe were still close friends. In the 1882 revision of his book, he talks about how his intention of updating his book was "frustrated" by the founding of the National American Kennel Club and how he had decided to leave the job of doing a stud book to that group. It was doubtless frustrating to Burges that the work on the NAKC's stud book had been so slow.

Rowe, and the NAKC, promised that a second volume would be forthcoming. In fact,

The National American Kennel Club Stud Book, Vol. II was not published until 1885. While the title page says that the volume was "printed by N. Rowe for The National American Kennel Club," the truth was that the club had ceased to officially exist. In 1884, its name had been changed to The National Field Trial Club and it was now concerned only with sporting dogs and field trials. In 1886, Rowe would issue, in quarterly installments, the third volume of his stud book, this time entitled The American Kennel Stud Book.Let me take a quick break for some shameless promotion. I have listed

Vol. I and Vol. II of the The National American Kennel Club Stud Book in our ebay store. With their limited press runs, they are among the very rarest of dog books. It's taken all my will to list these precious volumes for sale. Needless to say, for any collection which seeks to document the history of dogs in the United States, these books are an absolute MUST HAVE.

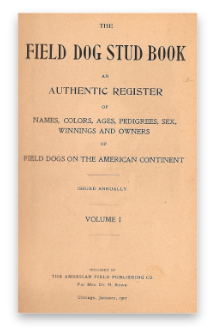

Before we get back to our story, I'd like to conclude with Dr. Rowe. In 1874, he began work on

The Field Dog Stud Book, published by The American Field. Once again, Dr. Rowe was ponderously slow in his work on this project. For the next 22 years he labored to compile the records, but it was still not done in 1896, when he died. His wife took over and the first volume was finally published in 1901. (You will find Volume I and Volume II in our ebay store. I'll be adding further volumes as time permits.)Okay, let's backtrack a little to 1879, right after the publication of the

National American Kennel Club Stud Book, Volume I. Enter: James Watson. He was a decided departure from the other gentlemen who were big names in the American dog world. He was a recent American immigrant and he did not breed Pointers or Setters. He was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on February 24, 1845 and died on March 8, 1915 at the ripe old age of 70. While Burges and Rowe had begun as professional men before turning their attention to writing, Watson had obtained a degree in journalism. He began breeding Collies while still in Scotland and he had an intense fascination with all breeds of dogs. Watson had attended early British shows and visited with many of the most prominent British breeders. Indeed, before coming to the U.S., in 1870, he is believed to have judged at early British shows. He would soon be tapped to judge shows in this country, too.

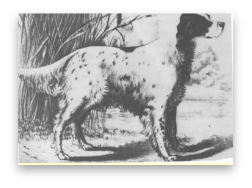

Druid, one of the first English Setters imported by Arnold Burges. One of the foundation dogs of the American Llewellins.

Richard Purcell Llewellyn

Watson promptly earned the ire of Burges, Rowe and their loyal followers with his views of what had become known and promoted as Llewellyn Setters. (The name would be spelled Llewellin in the U.S.) Watson had met Richard Purcell Llewellyn. He was well acquainted with his dogs and he was unimpressed. There was, in fact, Watson contended, no such thing as a pure Llewellin Setter. Mr. Llewellyn had begun by dabbling in Gordon Setters, had switched to Irish Setters and finally moved on to English Setters. He bought a few dogs from the Laverack strain and combined them with Setters from other breeders. While the Laveracks were carefully linebred, Watson felt that Llewellyn had demonstrated no real skill in breeding. His dogs were a hit or miss affair, with some very good specimens, but far more of mediocre type and field ability. Yet, the Llewellins were being promoted here as superior to all other English Setters. The adoration for them had become almost cult-like, with owners refusing to breed to anything other than another Llewellin. Those importing the Llewellins, Watson thought, were just easy marks for British breeders eager to make big bucks importing to gullible Americans. And, those Americans, were in turn making big bucks by promoting the superiority of the Llewellins. A puppy from one of Dr. Rowe's litters had sold for $1,000! (By the way, esteemed British writer John Henry Walsh, who wrote under the name Stonehenge, agreed fully with Watson's assessment of the Llewellyn dogs.)

(Note: Though the original Llewellins may not have been a strain in England, they would become one in the U.S.

Volume II of The Field Dog Stud Book, even included a separate and distinct registration category for Llewellin Setters.)