Page 2

The dog in the foreground is the famous English Collie

Ch. Charlemagne.That's a photo of him below.

Watson provided a vital link between American and British fanciers. He thought that those in the U.S. should begin their breeding programs with stock of the highest quality. He returned to England frequently, purchasing top dogs for many breeders. He was one of the first serious Collie breeders in the U.S. and one of the founding members of the Collie Club of America. He imported a bitch named Nesta, who arrived in whelp to the top-winning Collie Eng. Ch. Eclipse (son of Charlemagne). He was so pleased with that litter that he took Nesta back to England for a repeat of the breeding. From the second litter came the great Champions Glengary and Clipper. The sable and white Ch. Glengary would become a Best in Show winner and, while still a puppy, he was the first American-bred Collie to top the breed at Westminster.

(Click here to see Glengary's listing in the 1885 American Kennel Register.) In the first book on the breed, The Collie, by Dr. O.P. Bennett, originally published in 1917, and the revised, in 1924, by C.H. Wheeler, it says: "Perhaps the earliest of the American Collie fanciers was Mr. James Watson, of Hackensack, N.J....While he did not actively engage in breeding to the same extent that many others did, his opinions and advice were highly valued by all."

Watson was not a one-breed man, though. He was keenly interested in both Cocker and Field Spaniels and imported several for himself and others. In those early days, the two breeds had not be sorted out yet. Both were registered as "Cocker and Field Spaniels," yet they competed, as adults, in separate classes. Dogs over 28 pounds were entered as Field Spaniels and smaller dogs competed in the Cocker classes. He was one of the first to profile the English dog Obo, who would become the progenitor of the modern English Cocker Spaniel. He was also the first to sing the praises of Obo II, the English import who would transform the American Cocker Spaniel. "Obo II is a long way in front of any of his sex seen so far in this country either as a show dog or sire," he wrote in 1884. He would breed several bitches to Obo II. Watson was one of the founders of the American Spaniel Club, our oldest specialty club, established in 1881.

Being from Scotland, Watson was well acquainted with terriers and tirelessly promoted them. He imported the first Irish Terrier to this country. Before leaving England, she was bred to a top champion and made her show ring debut here in 1880. He would later tour Irish Terrier kennels in Dublin and bring back additional stock. He was one of the first to import Bob-Tailed Sheepdogs, as Old English were then known. In Watson's day they competed in the same classes as Collies. Watson quickly lost his enthusiasm for the breed, however, when his imported pair broke out of their run and killed his valuable Collie bitch, Nesta, along with her best daughter. He took an interest in Saint Bernards, in the days when imports from England and Switzerland were flooding the country. He imported a bitch, Margery, sired by the top winning dog, Bonivard, who had taken 40 prize cups in England. He gave Margery to his daughter as a present and she was bred at least twice, once to a Bonivard son. Bonivard was later imported to America where he continued his winning ways. In 1888, while in El Paso, Texas, he purchased a Chihuahua. Soon there would be a half-dozen of the rare dogs in his kennel.

The top winning Saint Bernard Bonivard. He won 40 prize cups in England

before being imported to the U.S. Watson would purchase a daughter

of Bonivard, named Margery, for his daughter.

James Watson's profession as a journalist provided him with a unique opportunity. He was able to both promote purebred dogs and to report on all the goings-on in the dog world. It was the era when each major city had multiple newspapers and, for the bulk of his career, Watson worked in New York and Philadelphia. Both cities were beehives of doggy activity, so Watson was in the midst of everything. He worked at various times at The New York Herald, The New York Express, The New York Sportsman, The Spirit of the Times and the New York Mail. Later, he would become editor of Country Life (which later became Country Life in America). For nine years, he served as the sporting and kennel editor for the Philadelphia Press.

Like most of the other dog fanciers in America, James Watson had eagerly anticipated Vol. II of the NAKC stud book. Most fanciers had figured that the books would be updated annually. In 1883, Watson took over as editor of the New York publication, Forest and Stream, where he devoted many of the pages to dog activities. He also found an opportunity to fill the vacuum left by the absence of an ongoing stud book. In that same year, he launched

The American Kennel Register, which began publication in April 1883. Not only was it the first U.S. magazine devoted exclusively to dogs, but it served as the very first all-breed registry. Each month's issue contained the particulars on dogs being registered and assigned them a registration number.The

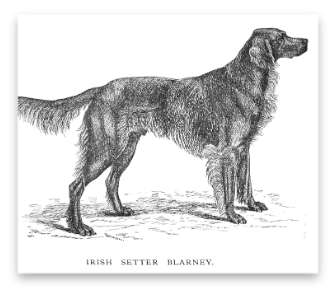

American Kennel Register isn't impressive when compared to today's glitzy dog magazines. But, it was remarkable for its time. Watson put all his journalistic skills to use, giving the Register the best editorial content of the day. (Interestingly, except for a few rare instances, Watson's name never appears as editor or the genius behind the publication. The author/editor was, however, well known at the time.) Watson penned reports on all the dog shows, comments on top dogs and reports on dogs imported. He answered readers questions. There were articles reprinted from British magazines and pieces on the various breeds penned by prominent British breeders. The Register was the first publication to report on the efforts to find vaccines for distemper and rabies. Watson took seriously his role as editor. When a number of dogs died after attending a Westminster show, he did everything he could to track down the story. His efforts in this regard earned him enemies in the Westminster inner circle who didn't want the deaths reported.No illustrations were included in the

1883 issues of The American Kennel Register. I'm not sure about 1884, but by 1885, Watson was including one or two beautifully drawn illustrations in each issue. Watson selected dogs that impressed him most at shows and hired artists to make drawings specifically for the Register. One of the drawings was usually a separate plate which was suitable for detaching and framing. Many readers did just. This explains why, though very few issues of the magazine have survived, it is still possible to find the plates available for sale. I have included several illustrations from the 1885 issues in this newsletter. I have not included the column on the Pointer, English Ch. Graphic, because it runs for three pages.Many of the wealthy owners who subscribed to the

American Kennel Register would save the year's issues and have them bound together in an annual volume. At year's end, the Register gave subscribers a title page with the volume number and date as well as an index to every dog registered. This was suitable for binding into the front of the book. It's possible that Forest and Stream, at least for the first year, may have sold a bound copy of the issues. In later years, they would offer binders for fifty cents which gave the outer appearance of professionally bound volumes.

It's clear when you read these priceless old issues of the Register that Watson saw himself as both a voice for and watchdog of the fancy at that time. He tried to ensure, as best he could, that the pedigrees of the dogs registered were accurate. He was appalled by the "Cross-Bred Setter" registrations included in both the Burges and NAKC stud books. It was a common occurrence to find registrations challenged and these were featured prominently in the pages of the Register. Watson went to lengths to track down the true story, often tapping his British contacts for help. These pedigree conflicts became the gossip items of the day and sometimes had to be settled by courts.

In the Burges book,

The American Kennel and Sporting Field, under the heading "Cross-bred and other Setters," one finds this explanation: "Owing to the indefinite character of some pedigrees it was impossible to decide to what breed certain dogs belonged. They are therefore included in the present class, under the head of 'Other Setters' to save discarding them altogether." The owners of some of those Cross-bred Setters were very prominent people and, one has to suspect, that that is why they were added to the stud books. Included among that list was a dog with a combination of English, Irish and Gordon blood owned by Major J.M. Taylor.