Newsletter 17

Edwin Megargee, Jr....

And the One That Got Away

June 6, 2011

Edwin Megargee, Jr....

And the One That Got Away

June 6, 2011

Like all inveterate collectors, I have stories about the one that got away. I bet you do, too. I've had some great finds in my 40 plus years of collecting. There are plenty of items worth hundreds of dollars, even a few worth thousands, that I got for a pittance. And, yet, I fixate on the ones that got away. I can't seem to turn loose of them. Even now, losing out on an auction at the last minute is enough to put me in a two-day funk.

There is, however, one gigantic miss that tops them all. Back in the mid-1970s, I saw an ad in a Miami paper for an estate sale. Included in the lengthy offerings were "dog paintings and prints." Hey, right up my alley! Harve was busy and, since I'm terrible at following street directions, I approached a friend to accompany me. She was reluctant, but I finally persuaded her. At the last minute, my van broke down and I couldn't make the auction.

The next day I got a call. "Remember that auction?" my friend said. "I hope you won't be mad, but I decided to go anyway. I really should have come over and picked you up, but I only decided at the last minute." She didn’t hear my gnashing teeth as her voice became excited. "You won't believe what I bought. Come over as soon as you can."

She swung the door open before I'd even knocked and ushered me into the living room. I took one step in and froze. Hanging on her wall was an oil painting by Megargee. I didn't even have to look at the signature to know who painted it. MEGARGEE...only my all-time favorite dog artist.

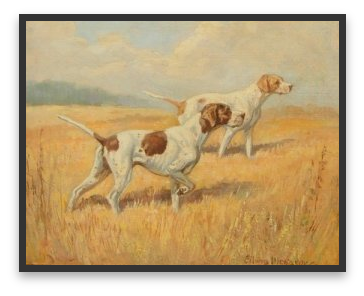

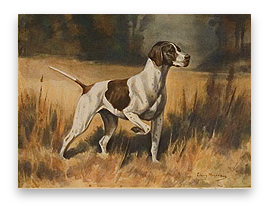

The painting was of two Pointers in a golden meadow. A liver-and-white male was poised in a classic point, foot raised, tail high. His conformation was exquisite...a finely chiseled head with a square muzzle, ears so soft they appeared to have been made of suede, you could see the muscles rippling and the tail seemed almost to quiver. Backing his point was a lemon-and-white bitch, a little more elegantly painted, but no less impressive.

I stood silently before the painting marveling at Megargee's brush strokes. It's one thing to see a photo of a Megargee painting or even to have one of his original prints. But absolutely nothing can compare to seeing, up close and personal, the actual brush strokes of a truly great painter.

I spent the rest of the afternoon in a chair a few feet from the painting. I couldn't be lured away by my friend's offer of lunch. She brought me a drink and left me alone in my vigil. I still recall that day when I sat alone and paid my own personal homage to this master of the craft.

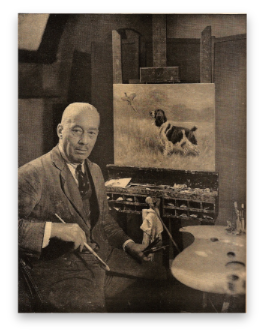

What is it about Megargee's dogs that strikes such a chord with me? I think it's the perspective that Megargee's life gave him. From childhood, he had been around quality dogs. He knew dog standards and the history of breeds. He understood that form followed function and why it was necessary for breeds to have certain characteristics. He hunted with bird dogs, hounds and terriers. He showed dogs of several breeds and was actively involved in all aspects of the dog world. He also bred dogs and I think this gave him a practical perspective and a commitment to emphasizing soundness and the key points of each breed.

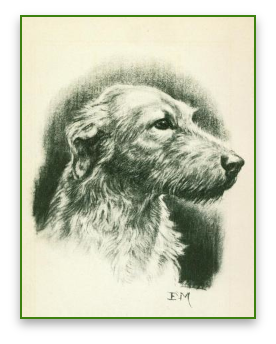

To me, one of the most appealing aspects of Megargee's work is his ability to infuse personality into the dogs he painted. "Personality is the hardest thing to put on canvas or cooper plate," he once said, "and unless the portrait shows the character of the subject, the artist has missed his biggest bet."

I stood silently before the painting marveling at Megargee's brush strokes. It's one thing to see a photo of a Megargee painting or even to have one of his original prints. But absolutely nothing can compare to seeing, up close and personal, the actual brush strokes of a truly great painter.

I spent the rest of the afternoon in a chair a few feet from the painting. I couldn't be lured away by my friend's offer of lunch. She brought me a drink and left me alone in my vigil. I still recall that day when I sat alone and paid my own personal homage to this master of the craft.

What is it about Megargee's dogs that strikes such a chord with me? I think it's the perspective that Megargee's life gave him. From childhood, he had been around quality dogs. He knew dog standards and the history of breeds. He understood that form followed function and why it was necessary for breeds to have certain characteristics. He hunted with bird dogs, hounds and terriers. He showed dogs of several breeds and was actively involved in all aspects of the dog world. He also bred dogs and I think this gave him a practical perspective and a commitment to emphasizing soundness and the key points of each breed.

To me, one of the most appealing aspects of Megargee's work is his ability to infuse personality into the dogs he painted. "Personality is the hardest thing to put on canvas or cooper plate," he once said, "and unless the portrait shows the character of the subject, the artist has missed his biggest bet."

"As far back as I can remember, I used to lie on my stomach and draw pictures of animals," he recalled in an interview for the American Kennel Gazette. "I think every small boy tries to draw dogs and cats because these are the creatures closest to his heart. The complete understanding between a small boy and his dog still seems rather wonderful to me."

By the time Megargee was 16, he knew what he wanted to do with his life. He announced to his father that he was going to be an artist. "I had quite a time persuading my father to let me study art. Being a lawyer, he seemed to think that art was a pretty shabby sort of profession. But, between you and me, I'm prone to believe that Father lived to be rather proud of my accomplishments."

In an attempt to please his father, Edwin Megargee, Jr. first enrolled at Georgetown. But, he couldn't keep up the pretense. After the first year, he returned home to Philadelphia and this time, with his father's reluctant blessing, enrolled at the Drexel Institute where he would earn an art degree. Years later, he would continue his studies attending the Art Students' League in New York City.

Megargee carefully studied animal anatomy. "Early in my career I determined to portray animals as they actually are and I studied the anatomy and structure of birds and animals until I could have articulated the skeleton of anything from a hen to a horse." Megargee realized that the basics were key when it came to drawing animals. "No success comes to the sketcher who has to worry over the mechanical details of his work. His drawing must be fundamentally sound and he positively must know canine construction."

Megargee's first job was working for a newspaper. These were the glory days when newspapers employed artists and had not yet began to rely almost solely on photographers. Here Megargee would learn the basics of illustration: grabbing the reader’s attention, selecting the most important points of a story, highlighting what was exciting, dangerous or touching.

In 1910, he was hired to illustrate a trio of books penned by Harold Bindloss, an eccentric Englishman. Bindloss has traveled around the world and settled in Canada where he began to write adventure stories, primarily about the West. Opium Smugglers, Boy Ranchers of Puget Sound and The Gold Trail became the first of more than 50 books that Megargee would illustrate.

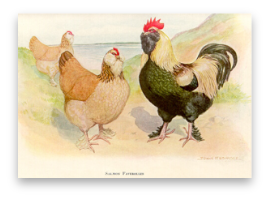

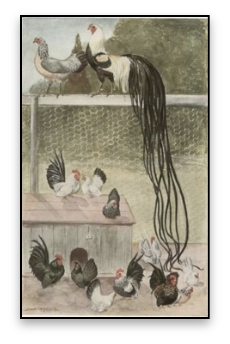

Megargee’s first big break came in 1911 when he was hired by the International Correspondence Schools, in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The company had developed a correspondence course for those interested in raising poultry. A total of 32 booklets were sent to those who enrolled in the course. Two of those booklets illustrated various types of fowl, from common breeds of chicken to pheasants to exotic fowl from around the world. Megargee’s illustrations are glorious. While some are simple depictions showing the differences between a cock and a hen, we begin to see one of the signature elements of Megargee’s later dog work. Megargee begins to paint his subjects in appropriate backgrounds: scratching the ground for food, poised before a farm gate, assembled around a water dish and atop a barnyard fence. The plates from these booklets are still highly collectible. They bear the 1911 date on the plates below Megargee’s signature, though the booklets were actually published in 1912. One can occasionally find surviving copies of these booklets which have been rebound in leather.

In 1921, the project was expanded and republished as The Book of Poultry, by Thomas McGrew, with 70 colored plates by Megargee. The brilliance of his correspondence school illustrations would also be noted across the Atlantic. Along with a number of British artists, Megargee’s illustrations were pegged by Charles Beebe to appear in his four volume Monograph of Pheasants. Volume I was published in 1918, but subsequent volumes were delayed by World War I. This limited edition of 600 numbered copies is considered by many to be the greatest ornithological work of the 1900s and, today, copies usually command $5,000-10,000.

Sometime between 1915 and 1918, Edwin Megargee, Jr. married Jean Inglee. Jean and Edwin were both dog lovers and the marriage would propel Megargee into the inner circles of the purebred dog world. Jean was the only child of Charles Topping Inglee, a man who had made a fortune in real estate. Inglee started out with English Setters, exhibiting his first dog in 1895, but he had become interested in Gordon Setters. Unfortunately, he was unable to find quality specimens in this country. His searches in Great Britain had come up wanting, too, but he finally located quality dogs in Norway, Denmark and Sweden. As virtually the only person promoting the breed, Inglee quickly gained prominence in dog circles.

Inglee established his Inglehurst Kennels, on his estate at Green Brook Township, New Jersey. He also maintained a plantation in North Carolina, where he would retire in winter and spring to hunt over his dogs. The first Gordon to bear the Inglehurst name was Joker, a dog who would finish his championship in eight days with three five point majors and go on to sire 20 champions. In 1924, Inglee was the driving force in the formation of the Gordon Setter Club of America. He would serve as Secretary of the Club from 1924-1929 and President from 1930-1937. He would also be the Club's first delegate to the AKC and hold that position from 1924 until 1941. Indeed, Charles Inglee would become known as the "Father of the American Gordon."

It was about this time that Megargee met Marguerite Kirmse. He fell in love with Kirmse's Scottish Terriers and soon became an avid Scottie owner. In 1924, Kirmse married Scottie breeder George Cole. (Cole would be elected President of the Scottish Terrier Club of America in 1934.) While she retained her New York studio, Kirmse settled on Cole's Arcady Farm, in Bridgewater, Connecticut, which housed a large assortment of terriers and sporting dogs. Kirmse and Megargee entered into a joint venture, breeding and showing Scotties under the Tobermory prefix. For a time, Megargee penned the Scottie column in the Gazette. Like the Megargees and Inglees, George and Marguerite Kirmse Cole would retire to a Carolina plantation in winter. Both artists found many wealthy owners who were eager to have them paint their dogs in the field.

In the 1920s, probably with the help of his father-in-law, Megargee began his involvement with the American Kennel Club. In those days, distant clubs were eager to have people in the New York area serve as their delegates at the annual meetings. Megargee would serve as delegate for the Capital City and Los Angeles Kennel Clubs and, in the 1930s, for the Louisiana Kennel Club. In 1926, he was appointed to the New York trial board and he became an AKC Director in 1928. In 1930, he obtained his AKC judging license and began judging the sporting and terrier groups.

Most artists struggled mightily during the Great Depression. Many survived only because of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration. His Public Works of Art program allowed hundreds of artists to keep working and brought extraordinary pieces of art to courthouses and other venues in cities and towns. In contrast, the Depression years were a time of prolific work for Megargee, though his son says that he struggled to make a living. Color plates in monthly magazines like Country Home and Field and Stream helped pay the bills and Megargee did a number of people portraits, too.

In the 1930s, Megargee produced some extraordinary work for the Derrydale Press. In 1931, Derrydale released four lithographs called Cockfighting Scenes. Once again, Megargee proven his mastery when painting fowl for these etchings crackle with excitement and activity.

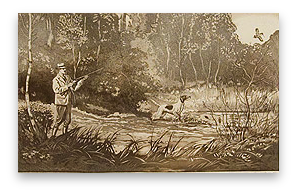

In the same year, Derrydale released the American Shooting Scenes series. These three 14 1/2 x 20 etchings included Grouse and Woodcock, which incorporate Pointers, and Pheasant which more prominently displays an English Springer Spaniel. These Derrydale etchings are highly collectable and command high prices.

These should not be confused with the shooting series of lithographs that was released by Field and Stream in about 1934. Sporting titles like Duck Shooting, Goose Shooting, Quail Shooting, Snipe Shooting and Grouse Shooting, they are distinct works and feature different breeds. Two of these appear above.

In 1935, Derrydale came out with two magnificent colored Megargee prints. Staunch depicts a Pointer and Steady features an English Setter. These lithographs came in a limited edition of 250 signed and numbered copies. They are the most collectible of all Megargee prints and seldom show up for sale. I know of one that showed up at an auction about three years ago and sold for $1,500.