Page 3

From April 1883 to January 1889, James Watson was probably the most listened to dog person in America. It's a shame that his contribution during this critical period is often missing from the doggy history books. As we will see later, that's largely a matter of the politics of the time. Indeed, if you read the history books, you'll see

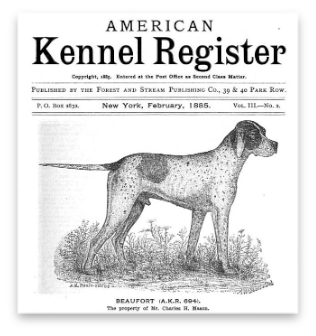

The National American Kennel Club Stud Book described as the first all-breed stud book in America. While not technically inaccurate, it paints a misleading picture. Like its predecessor, the Burges book, Vol. I, published in 1879, it was confined to sporting dogs. It contained mostly Pointers and the three Setter breeds, along with "Cross-bred and other Setters." It had a number of entries for Spaniels, principally Irish Water Spaniels and Cockers.There were a number of additional listings for Chesapeake Bay Retrievers. Next came Watson's the American Kennel Register which contains the first ever American registrations for all-breeds (i.e., including those outside the sporting group). In the first year, Watson registered dogs of 26 breeds. By 1887, that list had grown to include 32 breeds. (It would actually be more if we separated Cocker and Field Spaniels who were registered together at that time.) Watson's records were never published as an official "stud book." His contribution could have been forever enshrined in dog history, but for politics, as we shall soon discover. By contrast, Vol. II of the NAKC stud book, published in 1885, included 19 breeds, with four others lumped into a Miscellaneous designation. It also continued that odious classification of "Cross-Bred Setters." It's my contention that history has done a disservice to James Watson by labeling The National American Kennel Club Stud Book as the first all-breed stud book in the U.S.Time out for some additional shameless promotion. In my 40 years of collecting, I have been fortunate to acquire

Vol. I (1883), Vol. IV (1886) and Vol. V (1887) of The American Kennel Register. These are among my very favorite items in the collection. I will confess to you that, as I turn the pages of these rare issues, I get shivers. Interestingly, to my knowledge, only Vol. III (1885) has ever been reprinted. This was republished in a cheap edition in 2008 and can be seen free online by using Google Books. Before listing these volumes, I did a complete search of all the booksellers' databases, as well as a search using Google. I could not find a single issue or volume available for sale, other than the cheap edition mentioned above. It is with the greatest reluctance that I am offering these volumes for sale and, I warn you, I'm not letting them go cheaply. But, I made a promise to myself that I'd sell off the Dogcrazy Collection and so these extremely rare items are going up for sale, too.Many dog fanciers were furious, in 1884, when the National American Kennel Club changed its name to the National Field Trial Club and abandoned bench shows. Doubtless, the dog world had heard about their intentions before the official name change. In truth, Dr. Rowe, head of the Club, had never been much interested in bench shows. At that time, there were no standards for breeds and shows were judged by a variety of rules. Devising a system for bench shows had proven much more difficult than constructing a system for field trials.

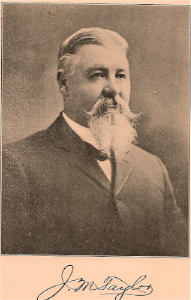

Major J.M. Taylor, head of the Tennessee Sportsman's Association, and Elliott Smith, an influential member of the Westminster Kennel Club, both talked of organizing a new national club, but there were conflicts. And, then a remarkable thing happened. A group of 25 fanciers presented a petition to James Watson to be published in The American Kennel Register. It appeared in the August 1884 issue:

Editor American Kennel Register:

In view of the conflicting actions of the Westminster Kennel Club and of Major Taylor relative to the inception of a National Kennel Club, and the danger of the proposal falling through thereby, we respectfully ask you to issue a call for a meeting of exhibitors and clubs to form such a Kennel Club, and that you prepare a plan of organization, work, etc., for such a club, to be considered at this meeting. It seems very desirable that the co-operation of so respected and distinguished a judge as Major Taylor, and so old and influential an organization as the Westminster Kennel Club, should both be secured to this project."

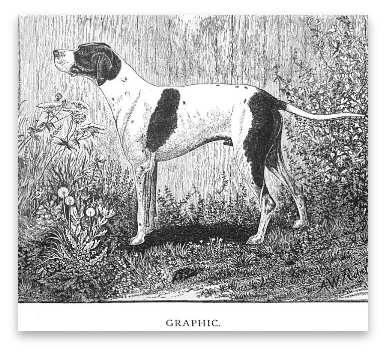

This petition put Watson, Taylor and Smith at the very center of the formative steps of what would become the AKC. It tasked Watson with preparing the plans and organization for the club, while securing the cooperation of Taylor and Smith. This was an impossible task. Both Taylor and Smith were gundog men. Taylor bred and promoted Llewellin Setters (and despised Watson for his views) and Smith bred Pointers. (Smith's wife did have a Collie she showed.) Taylor, you will remember, had owned one of those "Cross-Bred Setters" that Watson felt never should have been entered in stud books. Furthermore, Watson was appalled with some of the decisions Taylor made as a judge. (Later, in 1886, Watson would be dumbfounded when he watched Taylor place a lesser dog over the imported Pointer, the top winning Eng. Ch. Graphic. Watson had gone to England on two occasions before he finally arranged for the importation of this outstanding dog.)

I'm not sure if Taylor and Smith's response to the petition was printed in The American Kennel Register, since I don't have the issues from 1884, but I do have a tattered copy of The American Field, dated August 2, 1884, which gives their response: "We hereby issue an invitation to all kennel clubs and show associations to send a delegate to represent them at Philadelphia the second day of the show."

Was this idea of a "club of clubs" inspired genius or a direct jab at Watson? With his close links to Britain, it was well known that Watson favored a national club based on the model used by England's Kennel Club. He clearly felt that a club composed of individual members was more democratic. Was it an attempt by wealthy men from prominent families to control the fledgling American dog scene? Even in those days, Westminster was most definitely a high-brow, exclusive club. (For years, even up to the modern era, critics have charged that Westminster has too much influence in the running of the AKC.)

Whatever the motivation, Taylor and Smith immediately set out to undermine Watson's position. They enlisted that other Watson adversary, Dr. Rowe, in their campaign. Writing in the September 6, 1884 issue of The American Field, Dr. Rowe fired the first salvo: "The experiment of a club composed of individuals has been tried and failed. The National American Kennel Club was brought to life by us. We originated the idea...The National American Kennel Club demonstrated that a club of individuals has not been a success....This would not be the case with an association of clubs." (Of course, the individual member model was proving quite capable in England.)

The history books tell us that on September 17, 1884, representatives of the various dog clubs met in Philadelphia to form what would become the American Kennel Club. What they don't report was that there was another meeting held on September 16th, also at the Philadelphia Kennel Club show. That meeting, chaired by Watson, was composed of 75 people who were interested in an organization made up of individual members. Sadly, for Watson, some of Rowe's comments proved accurate. The meeting became unfocused and no decisions were made. Comments made by Watson, in the next few years, would convey his frustration at this abortive meeting.