Page 4

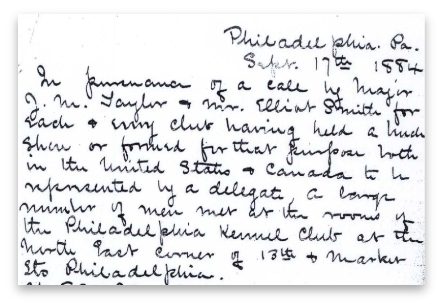

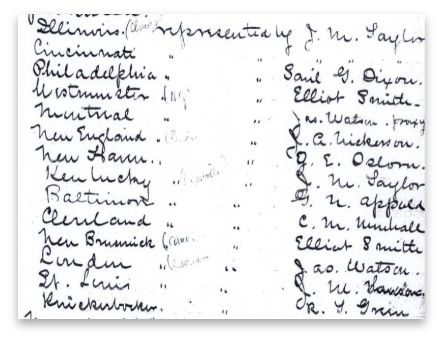

Representatives of 13 dog clubs from the U.S. and Canada attended the September 17th meeting. Interestingly, James Watson was there. He appeared by proxy as the delegate for two of the Canadian groups. Despite Watson's opposition to a "club of clubs," those present voted to form the National Bench Show Association and appointed a committee to draft a constitution and by-laws. The committee was to present these at their second meeting at the New York Non-Sporting Dog Show, in October.

Before that second meeting, in October, the name of the group was changed to the American Kennel Club. The constitution and the by-laws were adopted and officers were elected. Major Taylor was elected President and Elliott Smith was named First Vice-President. Watson was not elected to any office.

If you thought things went smoothly after this, you would be very wrong. Controversy and chaos swirled around the dog world. Major Taylor was not popular with many early dog fanciers. One of his first acts as President was to issue a new set of dog show rules that were so vague, confusing and illogical that they caused howls of protest from the AKC member clubs. Furthermore, he had announced them on his own without the input of the new member clubs.

There were no breed standards yet. Some clubs, including Westminster, had decided to use the standards set forth in the 3rd edition of Stonehenge's Dogs of the British Isles, revised in 1885. (Note: We have a copy of Stonehenge's 1888 continuation of this book,

The Dogs of Great Britain, America and Other Countries in our ebay store.) Often, though, judges made up their own standards. Early specialty clubs, including those Watson was involved in, were wrestling with establishing standards and you can imagine the controversy there was over this. Today, we think of "standards of perfection," which describe the "ideal" dog. In those early days, however, many people were more interested in molding the new standards to conform to their dogs.

There were no standards for judges, either, and the judging was often abysmal. At a Pittsburgh show, one judge had unilaterally made a class for "Maryland Bench Legged Beagles." In 1881, Arnold Burges took to the pages of the American Field, to excoriate the judging of his former friend, Major Taylor, in a front page editorial. He took readers through each and every decision Taylor had made and explained how he had royally bungled the judging. Watson was called in at one show to decide the top awards because the judges had botched things so badly. Watson lobbied for quality judges. At the very least, he urged, the best all-around judge on the panel should hand out the awards for Best Dog, Best Bitch, Best Brace, etc.

Many people accused judges of putting up their friends' dogs. Since judges were allowed to both judge and exhibit at the same show, many believed that deals were made for swapping top awards. Judges were also allowed to advertise and make deals to sell their own stock at the show. It was commonly believed that some judges could be bribed and others were said to have been intimidated into making specific choices.

Cheating was rampant among exhibitors, too. This took many forms, including altering color through the use of dye. One of the most common ploys was to substitute a top winning dog for the one actually named in the catalog. The poisoning of dogs was also rampant. Many exhibitors posted guards at their benches to watch their dogs around the clock. One top kennel used a small mutt that they would release into their kennel runs before letting their show dogs out. This way, the mutt could consume any poisoned meat that had been tossed over the fence at night.

Many of the people who had initially supported the AKC were ready to bolt. A few clubs did actually leave the fold in the following years. Watson, in the pages of the American Kennel Register, was one of the sharpest critics. Was he an instigator or did he reflect the sentiments of many dog fanciers of the time? Probably both. And, yet, when some people wrote in encouraging him to start a rival club, Watson urged them to give the AKC a little more time: "...it would be better to let the AKC alone for another three or four months, as there is good material for a club if it is utilized properly. We do not wish to be considered in opposition to the club until all means to get any good out of it have failed." But there was one thing that Watson was adamant about: Major Taylor had to go and he wasn't shy about saying so.

"The utter incompetence of the president to understand the duties of his office and his powers as president, and his long and uninterrupted series of blunders have rendered the club a laughing stock to all. Matters have got to such a pass that it is now simply a question of Major Taylor relinquishing office or the leading clubs resigning from the association. It is very well understood among the members of the New England, New Haven, Westminster, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh clubs that if there is a break they will go in a body, and that there will be a break unless Major Taylor resigns is just as certain."

The founders of the AKC may have despised Watson, but they listened to his comments and suggestions. When he analyzed Major Taylor's dog show rules and told why they wouldn't work and how they could be improved, most of his suggestions were implemented. He penned an indepth piece on every article in the AKC's constitution and by-laws, again offering suggestions. Many of these were accepted, too. Only seven months after the organization was founded, it was decided to move up the date of the annual meeting. This was primarily due to the move to oust Taylor as President. A vote was taken and Taylor survived, but only by six votes. When the board went into executive session, committees were appointed to formulate standards for breeds. For each breed, the officers assigned two or three prominent breeders and exhibitors. Taylor was appointed to the English Setter committee. Despite his expertise, particularly in Collies, Watson was not appointed to any of the breed committees.

Controversy and dissatisfaction continued to swirl and Taylor was at the very center of it all. A mere seven months later, another "annual" meeting was held and here Taylor presented his resignation. Smith was elected his successor. He would fill out Taylor's term and serve for one more year. (For many years, Smith would serve as Westminster's legal counsel and, in 1896, he would serve as show chairman.)